Colonel Bogey March

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Colonel Bogey March | |

|---|---|

| March by F. J. Ricketts | |

| Composed | 1914 |

The “Colonel Bogey March” is a British march that was composed in 1914 by Lieutenant F. J. Ricketts (1881–1945) (pen name Kenneth J. Alford), a British Army bandmaster who later became the director of music for the Royal Marines at Plymouth. The march is often whistled.

Featuring in films since it first appeared in The Lady Vanishes in 1938, Empire magazine included the tune in its list of 25 of Cinema’s Catchiest Earworms.

History

Since service personnel were, at that time, not encouraged to have professional lives outside the armed forces, British Army bandmaster F. J. Ricketts published “Colonel Bogey” and his other compositions under the pseudonym Kenneth J. Alford in 1914. One supposition is that the tune was inspired by a British military officer who “preferred to whistle a descending minor third” rather than shout “Fore!” when playing golf. It is this descending interval that begins each line of the melody. The name “Colonel Bogey” began in the late 19th century as an imaginary “standard opponent” in assessing a player’s performance, and by Edwardian times the Colonel had been adopted by the golfing world as the presiding spirit of the course. Edwardian golfers on both sides of the Atlantic often played matches against “Colonel Bogey”. Bogey is now a golfing term meaning “one over par”.

Legacy

The sheet music was a million-seller, and the march was recorded many times.

Colonel Bogey is or has been used as an official quick march by the following military units:

Australia

Australia

- 28th Battalion and its successor the 11th/28th Battalion, Royal Western Australia Regiment

Canada

Canada

New Zealand

New Zealand

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka

United States

United States

- Women’s Army Corps with lyrics written by Major Dorothy E. Nielsen

The tune was briefly used by a cad in the film “The Lady Vanishes” from 1938.

At the start of World War II, “Colonel Bogey” became a British institution when a popular song was set to the tune: “Hitler Has Only Got One Ball” (originally “Göring Has Only Got One Ball” after the Luftwaffe leader suffered a groin injury), essentially exalting rudeness.

In the 1947 feature film It Always Rains On Sunday, a pair of young would-be hooligans are interrupted in their trouble-making by an adult, and they march away whistling the “Colonel Bogey March” as a symbol of defiance and resentment.

In 1951, during the first computer conference held in Australia, the “Colonel Bogey March” was the first music played by a computer, by CSIRAC, a computer developed by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation.

The 1957 movie The Bridge on the River Kwai popularized The River Kwai March, a counter-march to Colonel Bogey March. In the 1961 movie The Parent Trap, the campers at an all-girls summer camp whistle the “Colonel Bogey March” as they march through camp, mirroring the scene from The Bridge on the River Kwai.

The square dance figure Grand Spin was written in 1967 and is performed to the music of the Colonel Bogey March.

In episode 28 (1976) of The Benny Hill Show, Sale of the Half-Century game show sketch, the march was used in a Name That Tune-style question. One of the contestants’ answers was “After the Ball” after which the host (Benny) responded with, “well, you’re sort of half-right” referring to the anti-Hitler slur.

The march has been used in German commercials for Underberg digestif bitter since the 1970s, and has become a classic jingle there. A parody titled “Comet” is a humorous song about the ill effects of consuming the cleaning product of the same name.

In the 1985 film The Breakfast Club, all the teenage main characters are whistling the tune during their Saturday detention when Principal Vernon (played by Paul Gleason) walks into the room. It was also used in Short Circuit and Spaceballs.

In The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air episode “I Know Why the Caged Bird Screams”, the fictional ULA Peacocks have a fight song to the tune of the Colonel Bogey March.

In the 2019, the Colonel Bogey March was used in the TV series The Man in the High Castle, in episode 8 of season 4.

The song was featured in episode 5 of season 6 of Outlander, revealing a returning character from season 5. The song also continued through the credits.

The Colonel Bogey March was used in the 2024 neo-noir television series Monsieur Spade from AMC and Canal+. Perhaps coincidentally, the main character, Sam Spade, was previously played by Humphrey Bogart, often called “Bogie”.

In Indonesia this march became the jingle tune for a medicine brand called Bodrex

The Bridge on the River Kwai

English composer Malcolm Arnold added a counter-march, which he titled “The River Kwai March“, for the 1957 dramatic film The Bridge on the River Kwai, set during World War II. The two marches were recorded together by Mitch Miller as “March from the River Kwai – Colonel Bogey” and it reached #20 in the US in 1958.

The Arnold march forms part of the orchestral concert suite made of the Arnold film score by Christopher Palmer published by Novello & Co in London.

On account of the movie, the “Colonel Bogey March” is often miscredited as the “River Kwai March”. While Arnold did use “Colonel Bogey” in his score for the movie, it was only the first theme and a bit of the second theme of “Colonel Bogey”, whistled unaccompanied by the British prisoners several times as they marched into the prison camp. A British actor, Percy Herbert, who appeared in The Bridge on the River Kwai suggested the use of the song in the movie. According to Kevin Brownlow’s interviews with David Lean, it was actually David Lean who knew of the song and fought during the screenwriting process to have it whistled by the troops. He realized it had to be whistled rather than sung because the World War II-era lyrics (see “Hitler Has Only Got One Ball“) were racy and would not get past the censors. Percy Herbert was used as a consultant on the film because he had first-hand experience of Japanese POW camps; he was paid an extra £5 per week by director David Lean.

Since the movie depicted prisoners of war held under inhumane conditions by the Japanese, Canadian officials were embarrassed in May 1980, when a military band played “Colonel Bogey” during a visit to Ottawa by Japanese prime minister Masayoshi Ōhira.

Jewel Thief (1967)

S.D. Burman used this composition in the 1967 Hindi spy thriller heist film Jewel Thief. The opening lines of “Yeh Dil Na Hota Bechaara” draw inspiration from the marching song.

The Bridge on the River Kwai (Film)

| The Bridge on the River Kwai | |

|---|---|

American theatrical release poster, “Style A”

|

|

| Directed by | David Lean |

| Screenplay by | |

| Based on | The Bridge over the River Kwai by Pierre Boulle |

| Produced by | Sam Spiegel |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Jack Hildyard |

| Edited by | Peter Taylor |

| Music by | Malcolm Arnold |

|

Production

company |

|

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

|

Release dates

|

|

|

Running time

|

161 minutes |

| Countries | United Kingdom United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2.8 million |

| Box office | $30.6 million |

The Bridge on the River Kwai is a 1957 epic war film directed by David Lean and based on the 1952 novel written by Pierre Boulle. Although the film uses the historical setting of the construction of the Burma Railway in 1942–1943, the plot and characters of Boulle’s novel and the screenplay are almost entirely fictional. The cast includes William Holden, Alec Guinness, Jack Hawkins, and Sessue Hayakawa.

It was initially scripted by screenwriter Carl Foreman, who was later replaced by Michael Wilson. Both writers had to work in secret, as they were on the Hollywood blacklist and had fled to the UK in order to continue working. As a result, Boulle, who did not speak English, was credited and received the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay; many years later, Foreman and Wilson posthumously received the Academy Award.

The Bridge on the River Kwai is now widely recognized as one of the greatest films ever made. It was the highest-grossing film of 1957 and received overwhelmingly positive reviews from critics. The film won seven Academy Awards (including Best Picture) at the 30th Academy Awards. In 1997, the film was deemed “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry by the United States Library of Congress. It has been included on the American Film Institute‘s list of best American films ever made. In 1999, the British Film Institute voted The Bridge on the River Kwai the 11th greatest British film of the 20th century.

Plot

In early 1943, a contingent of British prisoners of war, led by Colonel Nicholson, arrive at a Japanese prison camp in Thailand. US Navy Commander Shears tells of the horrific conditions. Nicholson forbids any escape attempts because they were ordered by headquarters to surrender, and escapes could be seen as defiance of orders. Also, the dense surrounding jungle renders escape virtually impossible.

Colonel Saito, the camp commandant, informs the new prisoners they will all work, even officers, on the construction of a railway bridge over the River Kwai that will connect Bangkok and Rangoon. Nicholson objects, informing Saito the Geneva Convention exempts officers from manual labour. After the enlisted men are marched to the bridge site, Saito threatens to have the officers shot, until Major Clipton, the British medical officer, warns Saito there are too many witnesses for him to get away with murder. Saito leaves the officers standing all day in the intense heat. That evening, the officers are placed in a punishment hut, while Nicholson is beaten and locked in an iron box.

Shears and two others escape. Only he survives, though he is wounded. He wanders into a Burmese village, is nursed back to health, and eventually reaches the British colony of Ceylon.

Work on the bridge proceeds badly, due to both the faulty Japanese engineering plans and the prisoners’ slow pace and deliberate sabotage. Saito is expected to commit ritual suicide if he fails to meet the rapidly approaching deadline. Desperate, he uses the anniversary of Japan’s 1905 victory in the Russo-Japanese War as an excuse to save face; he announces a general amnesty, releasing Nicholson and his officers and exempting them from manual labour. Nicholson is shocked by the poor job being done by his men and orders the building of a proper bridge, intending it to stand as a tribute to the British Army‘s ingenuity for centuries to come. Clipton objects, believing this to be collaboration with the enemy. Nicholson’s obsession with the bridge eventually drives him to allow his officers to volunteer to engage in manual labor.

Shears is enjoying his hospital stay in Ceylon unwittingly within a commando school referred to as “Force 316” (likely based on the real world Force 136 of the Special Operations Executive (SOE)). Major Warden of SOE invites Shears to join a commando mission to destroy the bridge just as it is completed. Shears tries to get out of the mission by confessing that he impersonated an officer, hoping for better treatment from the Japanese. Warden responds that he already knew and that the US Navy had agreed to transfer him to the British SOE with the simulated rank of Major to avoid embarrassment. Realising he has no choice, Shears volunteers.

Warden, Shears, and two other commandos parachute into Thailand; one, Chapman, dies after falling into a tree, and Warden is wounded in an encounter with a Japanese patrol and must be carried on a litter. He, Shears, and Joyce reach the river in time with the assistance of Siamese women bearers and their village chief, Khun Yai. Under cover of darkness, Shears and Joyce plant explosives on the bridge towers. A train carrying important dignitaries and soldiers is scheduled to be the first to cross the bridge the following day, and Warden wants to destroy both. By daybreak, however, the river level has dropped, exposing part of the wire connecting the explosives to the detonator. Nicholson spots the wire and brings it to Saito’s attention. As the train approaches, they hurry down to the riverbank to investigate. Joyce, manning the detonator, breaks cover and stabs Saito to death. Nicholson yells for help, while attempting to stop Joyce from reaching the detonator. When Joyce is wounded by Japanese fire, Shears swims across, but is himself shot. Recognising Shears, Nicholson exclaims, “What have I done?”

Warden fires a mortar, killing Shears and Joyce and fatally wounding Nicholson. Dying, Nicholson stumbles toward the detonator and falls on the plunger, blowing up the bridge and sending the train hurtling into the river. Warden tells the Siamese women that he had to prevent anyone from falling into enemy hands, and leaves with them. Witnessing the carnage, Clipton shakes his head and mutters, “Madness! … Madness!”

Cast

Chandran Rutnam and William Holden while shooting The Bridge on the River Kwai.

- William Holden as “Commander” Shears, U.S. Navy (later Brevet Major, Force 316)

- Jack Hawkins as Major Warden, Force 316

- Alec Guinness as Colonel Nicholson, British commander

- Sessue Hayakawa as Colonel Saito, Japanese commander

- James Donald as Major Clipton, medical officer

- André Morell as Colonel Green

- Peter Williams as Captain Reeves

- John Boxer as Major Hughes

- Percy Herbert as Grogan

- Harold Goodwin as Baker

- Henry Okawa as Captain Kanematsu

- Keiichiro Katsumoto as Lieutenant Miura

- M.R.B. Chakrabandhu as Yai

- Geoffrey Horne as Lieutenant Joyce

Production

Screenplay

The screenwriters, Carl Foreman and Michael Wilson, were on the Hollywood blacklist and, even though living in exile in England, could only work on the film in secret. The two did not collaborate on the script; Wilson took over after Lean was dissatisfied with Foreman’s work. The official credit was given to Pierre Boulle (who did not speak English), and the resulting Oscar for Best Screenplay (Adaptation) was awarded to him. Only in 1984 did the Academy rectify the situation by retroactively awarding the Oscar to Foreman and Wilson, posthumously in both cases. Subsequent releases of the film finally gave them proper screen credit. David Lean himself also claimed that producer Sam Spiegel cheated him out of his rightful part in the credits since he had had a major hand in the script.

The film was relatively faithful to the novel, with two major exceptions. Shears, who is a British commando officer like Warden in the novel, became an American sailor who escapes from the POW camp. Also, in the novel, the bridge is not destroyed: the train plummets into the river from a secondary charge placed by Warden, but Nicholson (never realising “what have I done?”) does not fall onto the plunger, and the bridge suffers only minor damage. Boulle nonetheless enjoyed the film version though he disagreed with its climax.

Casting

Although Lean later denied it, Charles Laughton was his first choice for the role of Nicholson. Laughton was in his habitually overweight state, and was either denied insurance coverage, or was simply not keen on filming in a tropical location. Guinness admitted that Lean “didn’t particularly want me” for the role, and thought about immediately returning to England when he arrived in Ceylon and Lean reminded him that he wasn’t the first choice.

William Holden’s deal was considered one of the best ever for an actor at the time, with him receiving $300,000 plus 10% of the film’s gross receipts.

Filming

Many directors were considered for the project, among them John Ford, William Wyler, Howard Hawks, Fred Zinnemann, and Orson Welles (who was also offered a starring role).

The film was an international co-production between companies in Britain and the United States.

Director David Lean clashed repeatedly with his cast members, particularly Guinness and James Donald, who thought the novel was anti-British. Lean had a lengthy row with Guinness over how to play the role of Nicholson; the actor wanted to play the part with a sense of humour and sympathy, while Lean thought Nicholson should be “a bore.” On another occasion, they argued over the scene where Nicholson reflects on his career in the army. Lean filmed the scene from behind Guinness and exploded in anger when Guinness asked him why he was doing this. After Guinness was done with the scene, Lean said, “Now you can all fuck off and go home, you English actors. Thank God that I’m starting work tomorrow with an American actor (William Holden).”

The film was made in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). The bridge in the film was near Kitulgala. The Mount Lavinia Hotel was used as a location for the hospital.

Guinness later said that he subconsciously based his walk while emerging from “the Oven” on that of his eleven-year-old son Matthew, who was recovering from polio at the time, a disease that left him temporarily paralyzed from the waist down. Guinness later reflected on the scene, calling it the “finest piece of work” he had ever done.

Lean nearly drowned when he was swept away by the river current during a break from filming.

In a 1988 interview with Barry Norman, Lean confirmed that Columbia almost stopped filming after three weeks because there was no white woman in the film, forcing him to add what he called “a very terrible scene” between Holden and a nurse on the beach.

The filming of the bridge explosion was to be done on 10 March 1957, in the presence of S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike, then Prime Minister of Ceylon, and a team of government dignitaries. However, cameraman Freddy Ford was unable to get out of the way of the explosion in time, and Lean had to stop filming. The train crashed into a generator on the other side of the bridge and was wrecked. It was repaired in time to be blown up the next morning, with Bandaranaike and his entourage present.

Music and soundtrack

| The Bridge on the River Kwai (Original Soundtrack Recording) | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by Various | |

| Released | 1957 |

| Recorded | 21 October 1957 |

| Genre | Soundtrack |

| Length | 44:49 |

| Label | Columbia |

| Producer | Various |

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Discogs | |

British composer Malcolm Arnold recalled that he had “ten days to write around forty-five minutes worth of music” – much less time than he was used to. He described the music for The Bridge on the River Kwai as the “worst job I ever had in my life” from the point of view of time. Despite this, he won an Oscar and a Grammy.

A memorable feature of the film is the tune that is whistled by the POWs—the first strain of the “Colonel Bogey March“—when they enter the camp. Gavin Young recounts meeting Donald Wise, a former prisoner of the Japanese who had worked on the Burma Railway. Young: “Donald, did anyone whistle Colonel Bogey … as they did in the film?” Wise: “I never heard it in Thailand. We hadn’t much breath left for whistling. But in Bangkok I was told that David Lean, the film’s director, became mad at the extras who played the prisoners—us—because they couldn’t march in time. Lean shouted at them, ‘For God’s sake, whistle a march to keep time to.’ And a bloke called George Siegatz … —an expert whistler—began to whistle Colonel Bogey, and a hit was born.”

The march was written in 1914 by Kenneth J. Alford, a pseudonym of British Bandmaster Frederick J. Ricketts. The Colonel Bogey strain was accompanied by a counter-melody using the same chord progressions, then continued with film composer Malcolm Arnold’s own composition, “The River Kwai March“, played by the off-screen orchestra taking over from the whistlers, though Arnold’s march was not heard in completion on the soundtrack. Mitch Miller had a hit with a recording of both marches.

In many tense, dramatic scenes, only the sounds of nature are used. An example of this is when commandos Warden and Joyce hunt a fleeing Japanese soldier through the jungle, desperate to prevent him from alerting other troops.

Historical accuracy

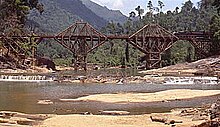

The River Kwai railroad bridge in 2017. The arched sections are original (constructed by Japan during World War II); the two sections with trapezoidal trusses were built by Japan after the war as war reparations, replacing sections destroyed by Allied aircraft.

The plot and characters of Boulle’s novel and the screenplay were almost entirely fictional. Since it was not a documentary, there are many historical inaccuracies in the film, as noted by eyewitnesses to the building of the real Burma Railway by historians.

The conditions to which POW and civilian labourers were subjected were far worse than the film depicted. According to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission:

The notorious Burma-Siam railway, built by Commonwealth, Dutch and American prisoners of war, was a Japanese project driven by the need for improved communications to support the large Japanese army in Burma. During its construction, approximately 13,000 prisoners of war died and were buried along the railway. An estimated 80,000 to 100,000 civilians also died in the course of the project, chiefly forced labour brought from Malaya and the Dutch East Indies, or conscripted in Siam (Thailand) and Burma. Two labour forces, one based in Siam and the other in Burma, worked from opposite ends of the line towards the centre.

Lieutenant Colonel Philip Toosey of the British Army was the real senior Allied officer at the bridge in question. Toosey was very different from Nicholson and was certainly not a collaborator who felt obliged to work with the Japanese. Toosey in fact did as much as possible to delay the building of the bridge. While Nicholson disapproves of acts of sabotage and other deliberate attempts to delay progress, Toosey encouraged this: termites were collected in large numbers to eat the wooden structures, and the concrete was badly mixed. Some consider the film to be an insulting parody of Toosey.

On a BBC Timewatch programme, a former prisoner at the camp states that it is unlikely that a man like the fictional Nicholson could have risen to the rank of lieutenant colonel, and, if he had, due to his collaboration he would have been “quietly eliminated” by the other prisoners.

Julie Summers, in her book The Colonel of Tamarkan, writes that Boulle, who had been a prisoner of war in Thailand, created the fictional Nicholson character as an amalgam of his memories of collaborating French officers. He strongly denied the claim that the book was anti-British, although many involved in the film itself (including Alec Guinness) felt otherwise.

Ernest Gordon, a survivor of the railway construction and POW camps described in the novel/film, stated in his 1962 book, Through the Valley of the Kwai:

In Pierre Boulle’s book The Bridge over the River Kwai and the film which was based on it, the impression was given that British officers not only took part in building the bridge willingly, but finished in record time to demonstrate to the enemy their superior efficiency. This was an entertaining story. But I am writing a factual account, and in justice to these men—living and dead—who worked on that bridge, I must make it clear that we never did so willingly. We worked at bayonet point and under bamboo lash, taking any risk to sabotage the operation whenever the opportunity arose.

A 1969 BBC television documentary, Return to the River Kwai, made by former POW John Coast, sought to highlight the real history behind the film (partly through getting ex-POWs to question its factual basis, for example Dr Hugh de Wardener and Lt-Col Alfred Knights), which angered many former POWs. The documentary itself was described by one newspaper reviewer when it was shown on Boxing Day 1974 (The Bridge on the River Kwai had been shown on BBC1 on Christmas Day 1974) as “Following the movie, this is a rerun of the antidote.”

Some of the characters in the film use the names of real people who were involved in the Burma Railway. Their roles and characters, however, are fictionalised. For example, a Sergeant-Major Risaburo Saito was in real life second in command at the camp. In the film, a Colonel Saito is camp commandant. In reality, Risaburo Saito was respected by his prisoners for being comparatively merciful and fair towards them. Toosey later defended him in his war crimes trial after the war, and the two became friends.

Some Japanese viewers resented the movie’s depiction of their engineers’ capabilities as inferior and less advanced than they were in reality. Japanese engineers had been surveying and planning the route of the railway since 1937, and they had demonstrated considerable skill during their construction efforts across South-East Asia. Some Japanese viewers also disliked the film for portraying the Allied prisoners of war as more capable of constructing the bridge than the Japanese engineers themselves were, accusing the filmmakers of being unfairly biased and unfamiliar with the realities of the bridge construction, a sentiment echoed by surviving prisoners of war who saw the film in cinemas.

The major railway bridge described in the novel and film did not actually cross the river known at the time as the Kwai. However, in 1943 a railway bridge was built by Allied POWs over the Mae Klong river – renamed Khwae Yai in the 1960s as a result of the film – at Tha Ma Kham, five kilometres from Kanchanaburi, Thailand. Boulle had never been to the bridge. He knew that the railway ran parallel to the Kwae for many miles, and he therefore assumed that it was the Kwae which it crossed just north of Kanchanaburi. This was an incorrect assumption. The destruction of the bridge as depicted in the film is also entirely fictional. In fact, two bridges were built: a temporary wooden bridge and a permanent steel/concrete bridge a few months later. Both bridges were used for two years, until they were destroyed by Allied bombing. The steel bridge was repaired and is still in use today.

Reception

Box office

The Bridge on the River Kwai was a massive commercial success. It was the highest-grossing film of 1957 in the United States and Canada and was also the most popular film at the British box office that year. According to Variety, the film earned estimated domestic box office revenues of $18,000,000 although this was revised downwards the following year to $15,000,000, which was still the biggest for 1958 and Columbia’s highest-grossing film at the time. By October 1960, the film had earned worldwide box office revenues of $30 million.

The film was re-released in 1964 and earned a further estimated $2.6 million at the box office in the United States and Canada but the following year its revised total US and Canadian revenues were reported by Variety as $17,195,000.

Critical response

On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film received an approval rating of 96% based on 93 reviews, with an average rating of 9.4/10. The site’s critical consensus reads, “This complex war epic asks hard questions, resists easy answers, and boasts career-defining work from star Alec Guinness and director David Lean.” On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 87 out of 100 based on 14 critics, indicating “universal acclaim”.

Bosley Crowther of The New York Times praised the film as “a towering entertainment of rich variety and revelation of the ways of men”. Mike Kaplan, reviewing for Variety, described it as “a gripping drama, expertly put together and handled with skill in all departments.” Kaplan further praised the actors, especially Alec Guinness, later writing “the film is unquestionably” his. William Holden was also credited for his acting for giving a solid characterization that was “easy, credible and always likeable in a role that is the pivot point of the story”. Edwin Schallert of the Los Angeles Times claimed the film’s strongest points were for being “excellently produced in virtually all respects and that it also offers an especially outstanding and different performance by Alec Guinness. Highly competent work is also done by William Holden, Jack Hawkins and Sessue Hayakawa”. Time magazine praised Lean’s directing, noting he demonstrates “a dazzlingly musical sense and control of the many and involving rhythms of a vast composition. He shows a rare sense of humor and a feeling for the poetry of situation; and he shows the even rarer ability to express these things, not in lines but in lives.” Harrison’s Reports described the film as an “excellent World War II adventure melodrama” in which the “production values are first-rate and so is the photography.”

Among retrospective reviews, Roger Ebert gave the film four out of four stars, noting that it is one of the few war movies that “focuses not on larger rights and wrongs but on individuals”, but commented that the viewer is not certain what is intended by the final dialogue due to the film’s shifting points of view. Slant magazine gave the film four out of five stars. Slant stated that “the 1957 epic subtly develops its themes about the irrationality of honor and the hypocrisy of Britain’s class system without ever compromising its thrilling war narrative”, and in comparing to other films of the time said that Bridge on the River Kwai “carefully builds its psychological tension until it erupts in a blinding flash of sulfur and flame.”

Balu Mahendra, the Tamil film director, observed the shooting of this film at Kitulgala, Sri Lanka during his school trip and was inspired to become a film director. Warren Buffett said it was his favorite movie. In an interview, he said that “[t]here were a lot of lessons in that… The ending of that was sort of the story of life. He created the railroad. Did he really want the enemy to come in across it?”

Some Japanese viewers have disliked the film’s depiction of the Japanese characters and the historical background presented as being inaccurate, particularly in the interactions between Saito and Nicholson. In particular, they objected to the implication presented in the film that Japanese military engineers were generally unskilled at their profession and lacked proficiency. In reality, Japanese engineers proved to be just as capable at construction efforts as their Allied counterparts.

Accolades

American Film Institute lists:

- 1998 — AFI’s 100 Years… 100 Movies — #13

- 2001 — AFI’s 100 Years… 100 Thrills — #58

- 2006 — AFI’s 100 Years… 100 Cheers — #14

- 2007 — AFI’s 100 Years… 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) — #36

The film has been selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry.

The British Film Institute placed The Bridge on the River Kwai as the 11th greatest British film.

Present day passenger train retraces the historical railway of WWII

Comments